The Gut Microbiome

1. Gut Microbiome

1.1 Facts and Figures about the Gut Microbiome

1.2 Functions of the Gut Microbiome

1.3 Composition of the Gut Microbiome

1.4 Influencing the Gut Microbiome

2. Gut Microbiome in Research

1. Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome consists of bacteria, archaea, and fungi and is a natural part of the human body. Its exact composition varies from person to person. Certain compositions can be classified as more beneficial or more detrimental. A microbiome that deviates from the healthy norm is associated with the occurrence of certain diseases. Gut bacteria perform numerous important functions, including training and influencing the development of the immune system, producing vitamins, protecting against pathogens, and much more.

1.1 Facts and Figures about the Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome accounts for roughly 1–2 kg of body weight, and the human body contains approximately as many cells as there are bacteria in the gut (1). This allows for an incredible enrichment of the genetic pool, resulting in a significant gain in functional capacity.

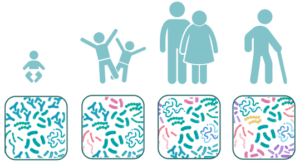

Each person’s gut microbiome is unique in its composition. Although this composition changes over the course of a lifetime (see figure), a certain core remains constant (2). This also highlights the fact that there is no such thing as a universally “normal” microbiome composition. However, the presence or absence of certain microbes is considered beneficial or disadvantageous. A microbiome that deviates from the norm is generally associated with a loss of beneficial bacteria and an overgrowth of less favorable species. Moreover, a “normal” or healthy microbiome is characterized by a high level of diversity.

1.2 Functions of the Gut Microbiome

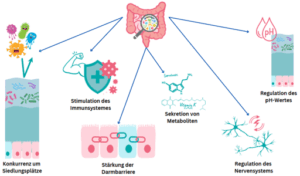

Among the functions of the gut microbiome is the defense against pathogens, as beneficial gut bacteria compete with harmful invaders for space and resources (3). In addition, gut bacteria produce vitamins, hormones, neurotransmitters, short‑chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and a variety of other metabolites (such as secondary bile acids and amino acids) that the human body can utilize (4, 5, 6). SCFAs also help regulate the pH of the gut and, in part, serve as an energy source for the intestinal epithelial cells (7). Another important role of the gut bacteria is to support and shape the development of the immune system (8). In this way, the microbiome has a pivotal influence on human health.

1.3 Composition of the Gut Microbiome

The composition of the microbiome can be assessed in various ways.

Bacteria can be classified into different groups based on their genetic characteristics. This is called “taxonomic classification.” This classification follows a hierarchical system with several levels: from domain to phylum, class, order, family, genus, and finally species. A central role is played by the analysis of the so-called 16S rRNA gene, which is present in all bacteria and changes only slowly over the course of evolution. By comparing the sequence of this gene, scientists can draw conclusions about the evolutionary relationships between bacteria.

Another way to classify bacteria is based on their morphological characteristics using the so-called Gram staining method. This divides bacteria into gram-positive and gram-negative groups, based on differences in the structure of their cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of murein (peptidoglycan) that retains the stain during the coloring process, causing them to appear purple under the microscope. In contrast, gram-negative bacteria have a thinner murein layer and an additional outer membrane, which causes the stain to be washed out during the process, making them appear red under the microscope.

1.4 Influencing the Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome is influenced by many different factors. The most significant among them are diet (including probiotics and prebiotics), antibiotics, and certain medications (10).

Probiotics are live microorganisms found in foods such as yogurt, kefir, or sauerkraut. They help maintain the balance of the gut flora and enrich it with “good” bacteria. Prebiotics are special fibers found in foods like onions, oats, flaxseeds, and many others. They serve as food for beneficial microbes in the large intestine and support their growth.

Carefully chosen foods thus help stabilize the ecosystem in the large intestine and promote health. However, when antibiotics are taken, this delicate balance can be disrupted, as they kill not only harmful but also important microorganisms.

By consciously selecting prebiotic and probiotic foods, the gut microbiome can be specifically supported, promoting the development of a diverse and healthy microbial ecosystem in the large intestine.

2. Gut Microbiome in Research

The human gut microbiome is gaining increasing importance in research. But why is that?

On the one hand, it has become clear that the microorganisms in the gut perform far more functions than previously believed. They are not only important for digestion and vitamin production but also play a central role in the development and regulation of the immune system, defense against pathogens, and even in influencing brain functions and behavior. On the other hand, connections have been observed between a disturbed gut flora and various diseases such as chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, diabetes, obesity, allergies, and neurological disorders. These insights open up new perspectives for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy, making the gut microbiome an exciting and promising field of research.

References

-

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016 Aug 19;14(8):e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. PMID: 27541692; PMCID: PMC4991899.

- Kundu, P., Blacher, E., Elinav, E., and Pettersson, S. (2017). Our Gut Microbiome: The Evolving Inner Self. Cell 171, 1481-1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.024.

- Aurora, R., and Sanford, T. (2015). Host Microbiota Contributes to Health and Response to Disease. Missouri Medicine 112, 317-322.

- Macpherson, A.J., Slack, E., Geuking, M.B., and McCoy, K.D. (2009). The mucosal firewalls against commensal intestinal microbes. Seminars in immunopathology 31, 145-149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-009-0174-3.

- Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Minireview: Gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014 Aug;28(8):1221-38. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1108. Epub 2014 Jun 3. PMID: 24892638; PMCID: PMC5414803.

- Spivak I, Fluhr L, Elinav E. Local and systemic effects of microbiome-derived metabolites. EMBO Rep. 2022 Oct 6;23(10):e55664. doi: 10.15252/embr.202255664. Epub 2022 Aug 29. PMID: 36031866; PMCID: PMC9535759.

- Rivière, A., Selak, M., Lantin, D., Leroy, F., and Vuyst, L. de (2016). Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Frontiers in microbiology 7, 979. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00979.

- Hooper, L.V., Littman, D.R., and Macpherson, A.J. (2012). Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science (New York, N.Y.) 336, 1268-1273. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1223490.

- Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms. 2019 Jan 10;7(1):14. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7010014. PMID: 30634578; PMCID: PMC6351938.

- Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, Zeller G, Telzerow A, Anderson EE, Brochado AR, Fernandez KC, Dose H, Mori H, Patil KR, Bork P, Typas A. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018 Mar 29;555(7698):623-628. doi: 10.1038/nature25979. Epub 2018 Mar 19. PMID: 29555994; PMCID: PMC6108420.